by Richard M. Rawlins

My first indoctrination to Adele Todd’s ‘Black Guard’ came, not from where it is currently on exhibition at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Trinidad and Tobago, but rather at a little early nineties basement night club in Diego Martin.

On my return from ‘school’ in Canada about ’91, I was taken to said night club in Diego Martin by a childhood friend tasked with integrating me back into life after ‘foreign’. Although I didn’t know it at the time, she would be my temporary tourist visa to this world to which I would later be denied access.

At the entrance to the club I was ‘braced’ by a rather large ‘BLACK GUARD’ and told without reason, “yuh cyah get in…” I was rescued by my friend who on realizing that I had not gone in behind her came out looking for me and told the guard, “He wid me. Steuppps. Wha’ wrong wid you?” The Guard’s retort was: “Ah dinna kno’. Cool cool, go on in, as is you.” Then came my first physical experience in about 10 years of feeling like a fly in a bowl of milk (ironic really considering that had I lived in Canada for decade before and never been faced by any sort of exclusion, racist or otherwise), and like the little lamb that Mary had, that club was white as Snow.

At the time, that club seemed like the place to be. This is a story that would be echoed throughout the nineties in a number of clubs that would have segregated nights: “coolie nights” and “niggar night” etc. It would even spark car-park-club protests by UWI students and lead to what I believe can only be described as ‘exclusivity by committee’, and secret venue clues like ‘You know where, let your shuttles take you there…’ All laughable now, it wasn’t to me then. So I set about figuring out how to gain access to this world with its exclusionary politics.

I applied for membership, something that concerned my father greatly as he wished I would just leave this alone instead of trying to make some idealistic point, (still basking in the post-university idealism glow I guess). This involved a two-page application that I had to fill out on the spot in the front office of a car rental establishment. I met all the criteria filled in the form and never got an answer or membership, after checking for two weeks. I got tired of checking to be honest, and went onto to re-integrate myself into places with people like myself and all-inclusive spaces, that were preferably outside and by the sea.

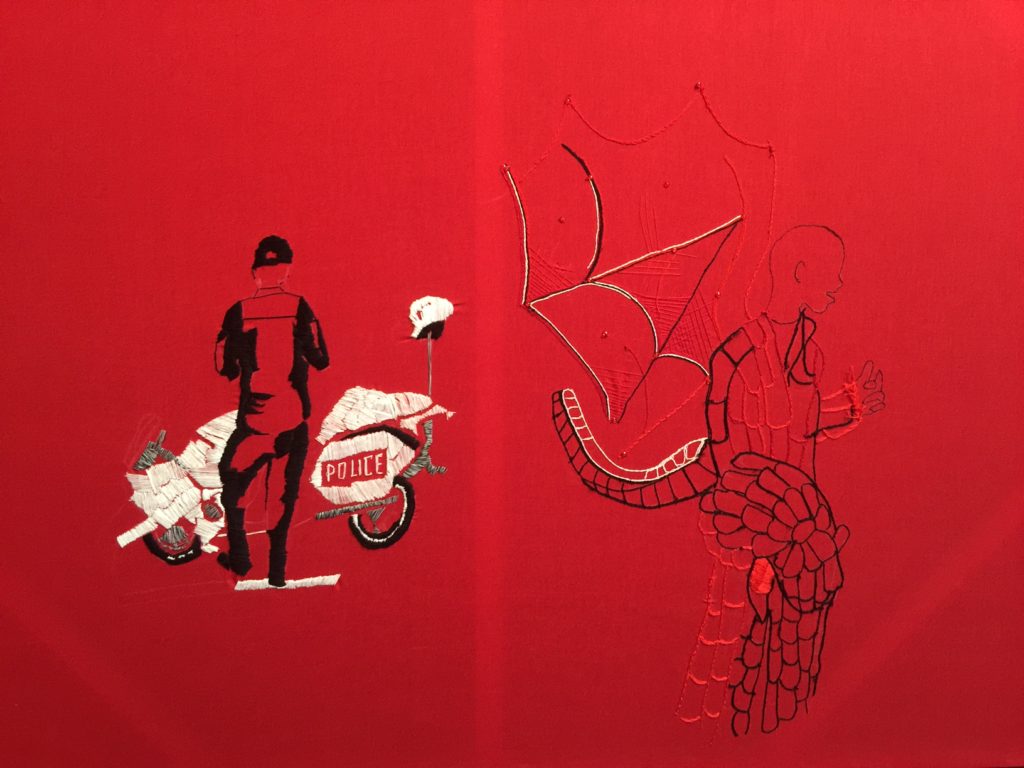

TWO POLICE WOMEN, detail.

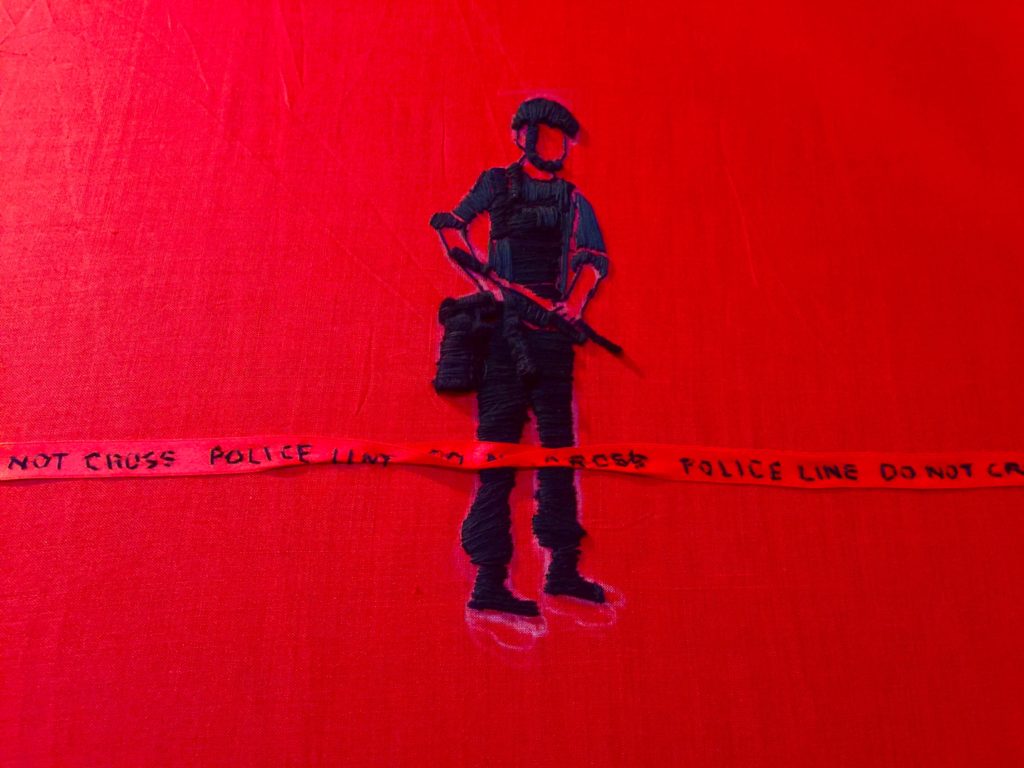

Adele Todd’s exhibition, Black Guard, presents us with a view of the state of security in our country. A responsibility that for the most part falls on the Afro-Trinidadian, read black people. Neatly couched in the lower front room of the National Museum, now painted red at the artist’s request (and with a National Flag at the center that turns the room into four imaginary chambers), the show is comprised of 26 pieces. The medium is embroidery, Todd’s stock in trade.

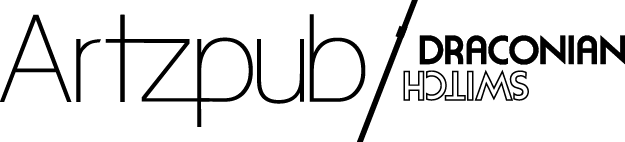

RED ARMY, detail.

Not a new thing as a form, the use of thread or yarn in works; artists such as Irénée Shaw, Che Lovelace, Ashraph, Kwynn Johnson, Pat Farrell Frederick and more recently Brianna McCarthy, have all used thread or yarn within their work – some utilizing thread as a metaphor to examine everything from sexuality, lines of communication, to physical and meta-physical lines of access, and others more concerned with examinations of the notion of a Woman’s Work and the elevation of such ‘decorative arts’ into the realm of serious art discussion. Todd’s use of it though is more extensive, it’s not an addition, embellishment or metaphor. Todd creates drawings with thread. While much has been written about the feminine arts and domestic process this work by Todd isn’t about that or even necessarily concerned with it. The pieces can be described as a series of symbols and drawings housing a double entendre and some humor.

One such pastiche of humour is Todd’s choosing to put the viewer’s gaze under scrutiny itself by installing four security cameras within the space.

WE ARE LOOKING AT YOU LOOKING AT THE ART. WATCH YOURSELF.

Todd’s cameras are plush, stuffed cloth, and are as non-functional as a lot of the security cameras we have out there on our city streets that never seem to be able to aid in the curbing of our society’s runaway crime problems.

CCTV

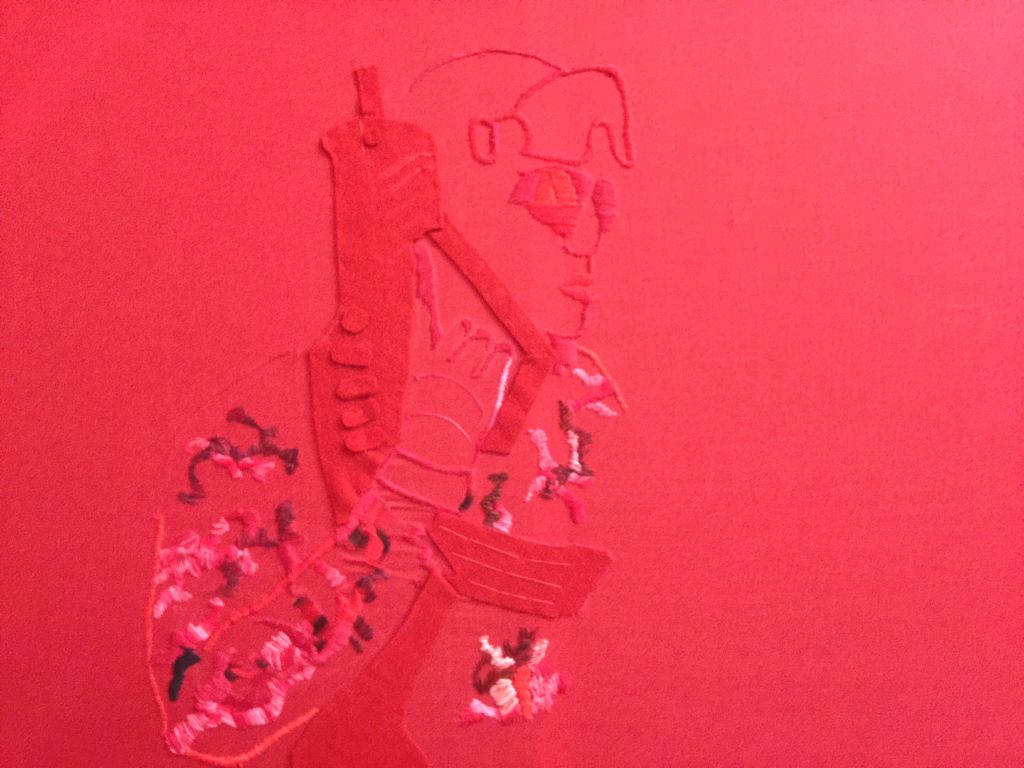

Another is a plush packet of du Maurier cigarettes and butts made by Todd out of felt and placed just under a large embroidery of prison officers entering the prison to begin their shift. There is a large sign in that drawing that lists among other ‘do nots‘ at the prison, NO SMOKING.

CIGARETTE BUTTS

People are stepping on my cigarette box (lol) so I might make a gate.- Adele Todd

The pieces, all white thread and black thread drawings on red linen, are fully sewn in some cases and in others partly finished, revealing Todd’s process and her chalk sewing guide lines. The red linen is stretched so tight you actually see the struts of the stretcher bars through it. In this way I believe, that Todd willingly asserts her own agenda around the making of an object. Will it still be considered art if you can see the under washes and pencil lines or in this case the artist chalk sewing guides? Will it still be art if it is not neatly packaged, on canvas, or embedded in an ornate baroque frame? Is it art if it’s shown in the National Museum and not in a commercial gallery space or for that matter the other way around? Somewhere in here for me though lies a little conundrum about the stretching of works: would they have been even more effective un-stretched and hung like tapestries or maybe even shrouds? But these are ultimately decisions for the artist.

PRISON SIGN, detail.

Hours before the opening of the exhibition, a rather well meaning ‘good samaritan’, obviously un-aware of artists and their deliberations and relationships surrounding their work, suggested to Todd that “we could get a wet rag and rub out the chalk lines and get a blow dryer and dry it off before people come. What you think?” The artist’s response: “Whattttt? ARE YOU OUT OF YOUR FRIGGING MIND?”

Delicate materials for delicate issues. This is not light work. If you’ve ever been involved in sewing anything (even socks), you would know that Todd’s venture here as is presented, is an ambitious and laborious one. This is not easy, in contrast to a willing acceptance of a ‘status’ quo that puts black people on the ‘outside’ of certain things that they were at one time responsible for creating. Two years of work went into this and began on her return from Glasgow where she had just finished showing an earlier work ‘Police an’ Tief,’ a visual investigation of crime and punishment in Trinidad and Tobago.

From her notes:

‘In a flash of inspiration, I saw our national flag and upon the flag, grainy images of our protective services. I felt compelled to continue my work with a new mandate. I would investigate the subject of those who take on the responsibility of keeping us safe.’

Todd, like a number of our artists, has a close relationship to themes surrounding Carnival, specifically the disappearance of the ‘traditional’ and the use of ‘MAS’ as a platform for performance. The latter is where Todd has had many successful and successive interventions over the years with her numerous provocative incursions into jouvay. What caused the destruction of man? 2010, saw the artist carrying around a large black box containing the fall of man. One had to pay to look inside the box. This intervention set up all kinds of discourses about the nature of sexuality, females as commodites, and the nature of ‘Mas and its role in the performative moment’. In 2009, Todd took to the jouvay streets with an Examination of the Herald by Audrey Beardsley, in it she wore a huge phallus.

Examination of the Herald by Audrey Beardsley

From her notes:

No woman in our carnival history had attempted to ‘wear’ a phallic piece, in all this time. Surely, we enjoy making light of our politics with the satire of the ‘Bomb competition’ during the wee hours of Lunde Gras. We wear the prosthetic breasts and bottoms, and men have extended the penis in play. But in all of the good fun, feminine imagery is blown up to an extreme of bikini mas. When women ‘play themselves’ they too seem to miss the irony of it all. So, amidst the good fun, I chose to cut a path with my attire, and the response was beyond my wildest expectations. Men were stunned and women giggled. No one passed me by without comment, and more often than not, the comments were close to me, for my ears alone. Pictures abounded, flashbulbs went off in abundance and people wanted to pose with me at every step.

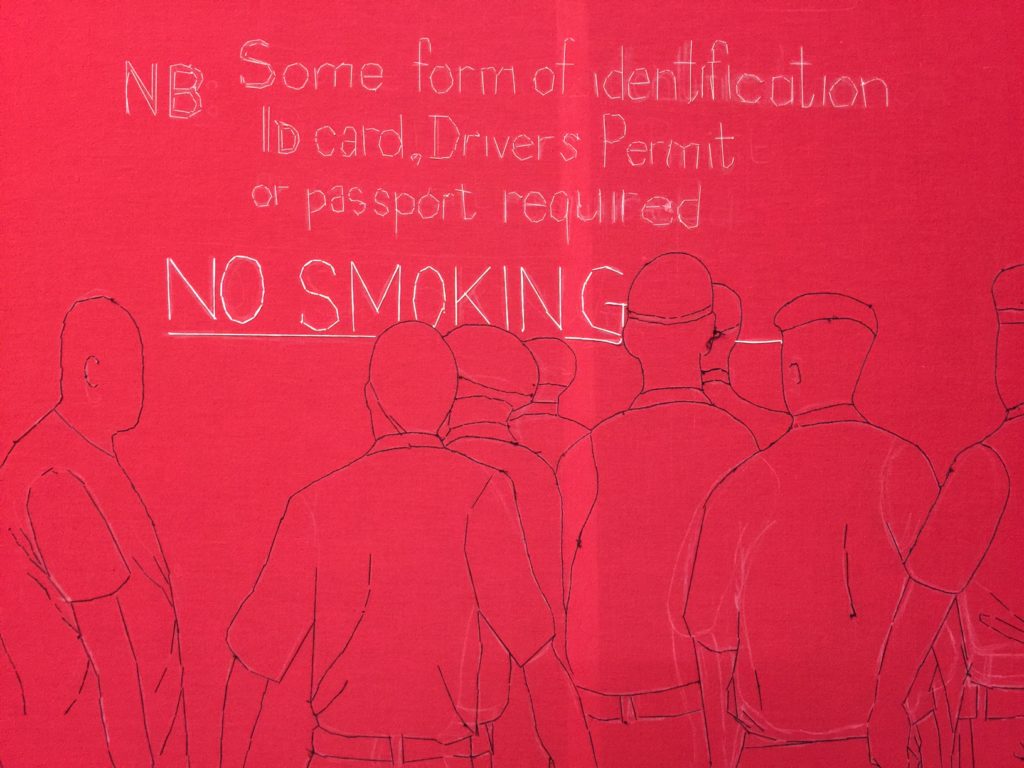

So there is no surprise that, in the exhibition, there are number of Carnival pieces that engage not the sexuality of Mas but rather the security of Mas. In one particular piece, an all too familiar scene of black men holding a rope to keep outsiders out of a band is presented for contemplation. Todd and I have had numerous discussions around this aspect of Carnival.

From Trinidad Guardian, February 10, 2016:

Carnival experience marred

“That aspect of our security and its extraction protocols are being reviewed. The members involved have been replaced. We are committed to serving our masqueraders and thank them for being with us,” the statement added.’

THE ROPE, detail.

We, (Trinidadians), speak about service in the country as though it were a bad word. Service and pride in your job and what you do seems to be lacking in some quarters, especially as related to our tourism industry. But this is not the case for the Carnival security. No, not at all. Quite the contrary, for there is a zealousness that comes with holding a rope, and defending masqueraders often much lighter shades of black than the security officers themselves from the on-looking crowds. Many a citizen has been beaten up by the ‘Mas Security’ (a lovely phrase, the meaning of which was not lost on Todd as it’s embroidered on to the figures holding the white rope while wearing white gloves), while attempting to cross an unwieldy band of thousands. Is the rope there to keep them in? Or keep allyuh out? Who exactly is the allyuh?

DRAGON

In another piece, a costumed Mas player portraying a ‘Dragon Mas’ is seen in the foreground as a motorcycle police officer looks off attending to his own concerns and paying him no mind. In stark contrast to the previous piece there is no intent on securing this player here. Maybe he isn’t deemed as of the same value of the ‘Beads and Bikini masquerader’ as alluded to in Todd’s notes, and maybe, he isn’t even seen as of a high enough threat level to concern the police office.

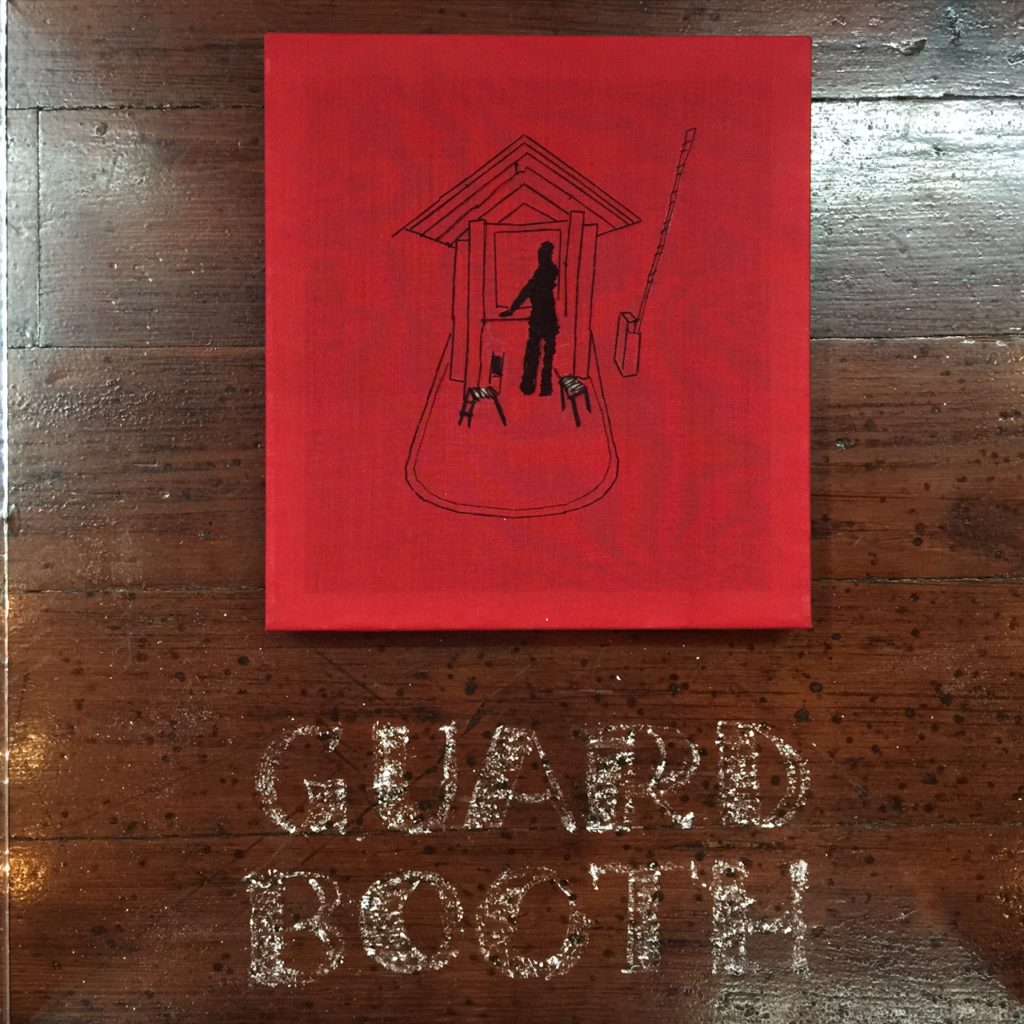

There is one work in the show that is literally on its own. By this I mean that it stands alone, under a glass box, on the floor of the exhibition space. There are one or two pieces of each sub-theme, maybe three within the show, (interesting considering the room size and it being painted red, which brings all the work literally pillar to post down on you in a bit of an overly intimate arrangement). The piece on the floor, ‘Guard Booth’, portrays a guard in a booth at the head of a gated community. The glass box creates a bit of magnification and at the same time gives the impression of being outside and having to look in, through a sort of force field. We can’t even think about entering there. Yuh doh see the guard?

Todd purposely stayed away from going down the road of multiple examinations with this as she felt it would lead her to a discussion toward access and gatekeepers, something she sees as a whole totally different exploration. The work is positioned diagonally to the flag, a nod perhaps to the many security guards that are often seen taking down National flags around the country at 6pm. These little juxtapositions within juxtapositions show Todd’s cleverness and her design sensibilities. Todd, an artist, educator and graphic designer by profession, understands design’s role in communicating through specific spaces and media.

THE PARADE GROUND

There is an odd ledge like area within the gallery space. Todd uses it to her advantage. Within this she sets up five works portraying different aspects of the annual Independence Day parade. Mostly depictions of columns of different members of our protective services. Although the pieces seem static in the representations, Todd embroiders and adjusts the dimensions of the characters placed within them to such an effect as to render the idea of the lines about to march off the parade ground. The work combined with the odd space creates a visual of the Independence Day parade ground as if from the President’s box itself.

One of these works, portraying female police, or as they are known in Trinidad and Tobago (and lovingly called) ‘woman police’, sets up a discussion around gender in the works.

WOMEN IN DRESS, detail.

Ah pullin’ way from she for she to hold meh tight

The woman police mus’ hold meh tight

An’ ah doing all of dat fo’ spite

for she to hold meh tight, tight, tight – Mighty Spoiler

There are numerous depictions throughout the exhibition of ‘woman police’, one such work depicts a ‘woman police’ weighed down with heavy tactical gear just like her male counterparts. This inclusion is very dear to me as my aunt (and coincidently, Todd’s dear family friend) Mavis Griffith was both a soldier and later the first ‘woman police’ in Trinidad and Tobago. And just as we speak of the role of the black man in the role of security so we must also acknowledge the black woman, not only their accepted roles as mothers and protectors, but also their crucial roles within our security forces as administrators, mentors, mavericks, humanists, and often the ones with cooler heads.

LONE FEMALE OFFICER

This whole discussion brings to mind a line I once read in my early advertising days. It was for a little half-page recruitment ad for female security guards. The headline read: Are you the measure of a man? Todd’s column of white and black thread women sets up that moment just before the ‘woman police’ leave the parade ground and march down Frederick Street. The moment that follows though, which is not captured by Todd, is that ‘pore raising’ moment when they actually hit the street and hundreds of women and little girls go crazy and begin screaming for the ‘woman police’ in a show of pride, as the ‘woman police’ go marching by, sub-machine guns across their chests, trying not to crack a smile at all the adulation being meted out on them.

There is a lot to be found in Todd’s Black Guard; it’s a work like that, which sets us up with a clear way of viewing. It’s a choice really: Black Guard or blackguard.

From her notes:

Blackguard, pronounced blaggard is an old-fashioned term for scoundrel.

Adele Todd – Black Guard opened on the 22nd of July and runs through 20th August at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain, Trinidad,