First published in the Trinidadian Sunday Guardian Arts Sunday, February 26, 2017

How do you see T&T? Does a nation forged in fires of hope still hold promise? Richard Mark Rawlins’ latest artwork uses iconography from the orphan Annie musical and the fuel of local politics to attend to concerns about personal and collective expectations for the future. “The sun will come out tomorrow,” sings Annie, “just thinking about tomorrow clears away the cobwebs and the sorrow ‘til there’s none.” In this interview with MARSHA PEARCE, Rawlins gives insight into his installation A Dress to the Nation-a work that is equally attractive in its ornamental appearance and irksome in its repetitive accompanying soundtrack. Rawlins points to a tomorrow steeped in appeal and frustration. In speaking about his work, he also shares his views on the politics of art and culture.

MP: You often include words in your artwork, with some pieces exploiting meanings and ambiguities, putting a spotlight on wordplay. Tell me about your fascination with words in the context of your art making practice.

RMR: I live and work as a graphic designer; it was how I was trained. I am accustomed to communicating visually with words and images. I love typography, mass communications, and printmaking. I think of letters as texture. Art, like design, is work. I started using words in my work as a way of connecting the dots. It is a narrative approach to design, which I incorporate into my art. This seems natural to me since we are surrounded by words: mauvais langue, picong, patois, dancehall lyrics, soca, kaiso, good and bad sign painting, fete sign culture and the fact that we speak with our hands when relating a story.

I am always pushing to be able to speak to people in my work, always seeking to break the passive nature of viewing art. Words help me share my sketchbook thoughts and opinions and, in some cases, issue a challenge to the viewer to go deeper than the surface and look for their own story. I am literally trying to make art that ‘speaks’ to people, as language has the potential to serve as an art form. The thing about it is this: once the words are there, it’s hard to avoid reading them. In the context of a white cube or alternate gallery space the WORD may actually have more power than in the pages of a magazine or a book.

How did the idea for this new work come about? What was your intention for the work?

A Dress to the Nation is commentary. The idea to do this came about sometime ago while I was watching a recap via social media of an address to the nation by our Prime Minister. It started me thinking about the importance of the term “an address to the nation” and what it means today.

For one thing, in my 50-year span, I’ve seen countless addresses to the nation. As a child I remember hustling home with my family to make sure we did not miss whatever important thing was going to be said. I was too young to understand what it meant then. As I got older and more politically aware, I realised they had come to mean responses to public outcry, a clear position on an unwavering policy of some sort, the announcement of a coup, an explanation of how the country’s coat of arms managed to get onto a bottle of champagne, or to reassure a nation, that things will get better. An address was an opportunity to say: “It’s a little rough right now, but it will get better-tomorrow not today, it will be better. Maybe.”

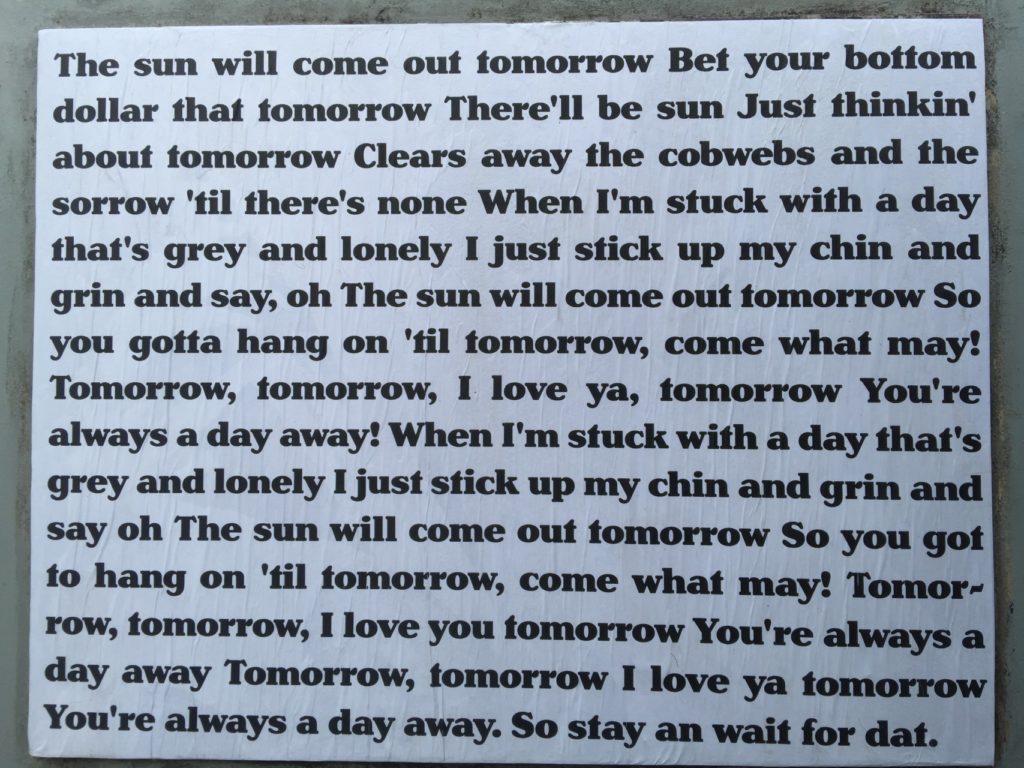

Well I’m significantly older now, and ironically, the addresses to the nation don’t seem to hold the power they once had. Social media has eliminated the need to hurry home to hear the address at a specific time, and the public seems to be even more confused after the address than before it began – if one goes by the comments on social media anyway. So I decided I would design and make a dress out of enough material to make two national flags, and incorporate some lace and frou-frou into it so that it would be a Trinbagonian contemporary art take on the little orphan Annie dress. There’s a big bow on it and everything, a real fancy, pretty thing. I designed the dress and had my friend, fashion designer Lisa Gittens, fabricate it for me as I can’t sew. Well, I can sew a little bit but I can’t sew-sew.

Then I created a soundtrack to go with the installation. I added an irritating 11-hour loop of the song Tomorrow from the movie Annie, and threw in my daughter’s old tap shoes and that was it. The tap shoes are a nod to the Annie musical and they complete the outfit. However they also suggest the idea of tap dancing around issues or maybe tap tapity tap tap as we wait and wait. As intentions go, I’d like people to see it and really begin to think about what these promises of “hope” mean for our country. It’s a personal narrative for all of us really. The original working title for the piece was A Dress to the Nation: Hope and Fear at the Edge of Feasibility.

What do you see as some of the politics – power machinations – of the art scene in T&T?

I have a question written on my studio wall: “How do we escape the gatekeepers?” I’ve learned it is the tree in the forest thing. If you aren’t aware of any gatekeepers, do they exist? The answer for me is, no. Well, that’s what I thought. Then I applied for a local fund aimed at cultural producers. It was my intention to produce a book about my recent exhibition Finding Black. After a month of not hearing any word, I called only to be politely informed: “Nah yuh didn’t get through. We can’t help you at this time.”

Now you probably will never see a painting with the words “I AM NOT YUH N—A” on a T&T High Commission wall or an embassy or a nice family restaurant, and the work I produce doesn’t fall under what is considered “culture,” and maybe it makes people uncomfortable. Yet, why must consideration only be given to funding Best Village, chutney and Carnival shows and historical documentation? Is the pursuit of “CULTyah” the only realm of understanding in our art space? If, as writer James Baldwin noted, the artist’s job is to disrupt the public space, then am I not doing my job?

I guess, in a nutshell, the real ‘power machinations’ are those that would see the ‘contemporary’ and the ‘conceptual’ as useless, or worse, dangerous while establishing a safe position of conservatism for our society, based on their own capitalist ideals or agendas. They are a problem. I will leave you with this: I once heard a Minister of Culture tell the audience at a book launch: “I used to draw yuh know but, I give that up. It didn’t have no money in that.”

Richard Mark Rawlins’ A Dress to the Nation was installed at Alice Yard, 80 Roberts Street Woodbrook, Port-of-Spain, and was available to the public any time from March 3- 8. Audiences could also find a related poster design by Rawlins at Alice Yard’s adjunct space known as Granderson Lab, 24 Erthig Road, Belmont.